If you’ve ever wandered around a liquor store or the alcohol section of many groceries, you’ve no doubt seen how many different bottles of wine are available for purchase. Unless a consumer has previously tried a particular bottle or had one recommended by a trusted friend, how is a consumer supposed to choose a bottle? After all, from the hundreds, even thousands, of different wines available, there are dramatic differences in quality and taste, not necessarily associated with price.

Better liquor stores (and even more so with wine shops or liquor stores specializing in wine) have employees (or proprietors) who are familiar with as many of the wines as possible and, even if not familiar with a particular bottle, usually have some knowledge of the producer or other information from which they can help a consumer make an informed decision. The best employees of the best wine shops and liquor stores know the right questions to ask of customers to learn their particular palates in order to recommend appropriate wines. But at your run-of-the-mill liquor store or grocery store, there is simply no way to have employees this knowledgeable about the wines and customers or willing or able to devote the time (and expense) to learn about the wines and customers. Try asking an employee at most grocery stores whether a particular bottle of wine is any good and you’ll most likely get a blank stare or a simple “Uh, I dunno”.

My mother used to own a women’s clothing store. One of her strengths was knowing her customers’ tastes (not to mention what they’d previously purchased). Thus, if a husband came into the store and wanted to buy his wife a present, my mother could direct him to something that she knew the wife would like (and look good in and didn’t already own). A similar philosophy must work for a wine store: If the proprietor learns what I like and consistently recommends wines that I do, in fact, enjoy, then I will continue to respect and follow his advice (and shop at his store). By contrast, if the proprietor recommends wines that I do not like or doesn’t take the time to learn my palate, then I have no reason to trust his recommendations (or frequent that store).

But not everyone has the time to develop a palate, to shop at a specialty wine store, to get to know the proprietor (or allow the proprietor to get to know them), or, perhaps most importantly, to spend much money for a bottle of wine. How then can a consumer decide which of the numerous bottles available at the local grocery or regular liquor store to buy? How do you separate the good from the mediocre from the swill?

One method employed by many stores (and eschewed by many others) is the “shelf-talker”. This is usually a small note displayed by the bottle to tell the consumer what to expect from that particular wine. Within the wine community, there is some controversy about the use of shelf-talkers. For myself, I recognize the usefulness of shelf-talkers, but am often wary. A recent incident (discussed at the end of this post) led me to take the time to write about shelf-talkers.

On the positive side, the use of shelf-talkers can to some extent help a consumer with no other information “get into the game”. If the store carries 500 different bottles of wine, there would most likely be no other way for a consumer to make a choice other than buying based solely on price or brand name. But in the case of wine, more so than almost any other product I can think of, there is far, far more than just price or brand that needs to be considered. You can buy a lot of very good wines for $10; but you can buy even more bad wines for that price. You can also buy a lot of very bad wines for far more money. And a winery that makes a very good $10 Merlot doesn’t necessarily also make a good $10 Riesling, so reliance upon brand doesn’t work quite so well, either (and add to this the fact that many brands make only one or two varieties and thus may have no brand recognition beyond wine connoisseurs). Plus, just because that Merlot was good last year doesn’t mean that it will be good this year.

So when a consumer walks into a store that does use shelf-talkers, they can be quite helpful. Knowing that a particular wine won a medal at a prestigious wine competition or was highly recommended or considered a best value by a respected wine magazine can do quite a lot to help a consumer make an informed decision. If there are 20 bottles of $10 Merlot and one of them received a “Smart Buy” rating from Wine Spectator and another has a 92 rating from Wine Enthusiast, then the consumer at least has something on which to base a decision and a reason to choose one wine instead of another. (I’m not going to get into the issue of how various wine magazines make their ratings or whether there is bias; that is a complicated and controversial enough issue for another day.) So, in that respect, shelf-talkers can be a valuable aid to consumers. Similarly, a shelf-talker that helps a consumer know what to expect from the wine or suggest food pairings can also be quite useful (especially for a consumer interested in trying a more “exotic” wine).

Given that, why would a store choose not to use shelf-talkers (presuming that it doesn’t have knowledgeable employees)? Here’s one simple reason: Take two bottles of Merlot, one costing $10 and the other costing $20. Now presume that the $10 bottle gets better ratings (or wins more awards, or whatever) than the $20 bottle. How many consumers are going to choose the lesser-rated, more expensive bottle? Obviously, the store has more incentive to sell the more expensive bottle.

So a shelf-talker can provide good information to a consumer, but not necessarily to the benefit of the store.

But there are downsides to consumers, too (and, unfortunately, these may be to the benefit of retailers).

First, many stores that do use shelf-talkers, use them selectively; that is, only some wines have an associated shelf-talker. How does the store decide which wines will get shelf-talkers and which won’t? One possibility is that poorly-rated wines don’t get a shelf-talker while highly-rates wines do. However, experience suggests that this reasoning is not employed. I’ve seen plenty of stores with shelf-talkers on mediocre wines while very good wines have no associated shelf-talker. Thus, when a consumer sees selective use of shelf-talkers, the consumer should at least consider why the store has chosen to use them only selectively. Why this bottle, but not that bottle? Perhaps the use of a shelf-talker is more indicative of wines that the store is working hardest to sell (perhaps there is a glut in the storeroom or the store got those bottles at a particularly good price). Or perhaps the store has been paid by a particular winery or wholesaler to utilize shelf-talkers for its wines. In some respects, use of a shelf-talker may not be much different than the way the grocery chooses to put a particular brand of cookie or soft drink in its Sunday circular.

The other downsides for consumers are more troubling, sometimes (as we’ll see), even fraudulent.

Many stores use a shelf-talker that recites ratings (usually from wine magazines) for the past several vintages. For example, at Fresh Market or Costco, you’re likely to see a shelf-talker that says something like this:

2007: No rating

2006: 90 Wine Spectator

2005: 91 Wine Enthusiast

2004: 88 Wine Spectator

Generally, that shelf-talker is “fair”. But what if the 2007 vintage has been rated subsequent to the time that the shelf-talker was printed? If the wine got a good rating for 2007, I guess it’s mostly a case of “no harm, no foul”. But what if the 2007 vintage received a poor rating? If the store is trying to sell the wine on the basis of past good ratings, then isn’t the more recent poor rating relevant? Certainly, the store shouldn’t be expected to revise shelf-talkers daily, but shouldn’t a consumer be able to expect that a statement that a particular wine hasn’t been rated is at least a reasonably up to date statement?

This example above also illustrates another frequent problem. Note that the 2004 and 2006 vintages cite Wine Spectator while the 2005 vintage cites Wine Enthusiast. Why? Maybe the 2005 vintage wasn’t rated by Wine Spectator; if not, it is certainly fair to cite another source for a rating. But what if Wine Spectator’s rating for 2005 was 82? In this case, is it fair to cite good ratings from one source but when that source gives a poor rating to change to a source that gave a better rating? On one hand, as long as all of the sources are reputable, what’s wrong with choosing the source that gave the best rating? On the other hand, something just seems “wrong” with changing sources mid-stream, when the only reason is to avoid noting a poor score.

Shelf-talkers like that in the above-example are also known to employ an additional bit of deception. Occasionally, you’ll see the list of vintages omit a particular year. In my experience, that is almost always a sign that the store is trying to hide a bad rating for a particular vintage (rarely it is because that particular wine was not produced that particular year). This practice also seems “wrong”; moreover, I don’t really understand this practice given that the store is not trying to sell the wine that received the bad rating anyway.

Another thing to look for on these kinds of shelf-talkers is the use of lots of different sources for ratings, especially sources not usually considered among the “usual suspects”. Different people have different opinions about the ratings of different sources, but generally Wine Spectator, Wine Enthusiast, and Wine Advocate (Robert Parker) are reasonably well-respected. Wine & Spirits and Steven Tanzer are also reasonably well-respected, though not used as commonly as the first three. But there are numerous other sources that you may see on shelf-talkers from time-to-time. Unfortunately, most consumers who don’t read wine trade magazines have no idea who these sources are and have no reason to respect one more than another. So query the “fairness” of using the lesser-known sources. It’s a bit like when a newspaper prints a movie review by the reviewer for the North Podunk Post rather than a review from the New York Times or one of the well-known reviewers from one of the major papers or magazines. Why should a consumer give any credence to that reviewer’s opinion? This issue may be exacerbated in the case of wine magazines where there is a lot of speculation (maybe even evidence) that some sources (maybe even the well-respected sources) employ a “pay-for-play'” methodology; that is, wineries who advertise with that periodical tend to get more favorable treatment. Maybe yes, maybe no. But certainly it would be improper for a shelf-talker to quote a periodical where the reviews are not presumed to have some degree of impartiality and independence.

Another common “trick” employed on shelf-talkers is to mention awards that a particular wine has won. “Gold Medal at 2008 Santa Fe Wine Competition” for example. Here’s the problem: Is the Santa Fe Wine Competition a good competition? Is it even a real competition? If I tell you that a film won an Academy Award, you know what that is and you know that’s an impressive achievement. Of course, if I failed to mention that the award was for editing, rather than for best picture, you’d probably be a bit miffed. And what if I tell you that a movie won the Journalist’s Guild Achievement Award (no such thing as far as I know…)? In the world of wine, there are hundreds if not thousands of contents and awards a wine could wine, but how many are really important? But if you don’t follow wine closely, how would you know which of those awards are meaningful? Recently I was shopping at a reputable wine store with good, knowledgeable staff. I asked about a particular bottle and the clerk laughed and told me that it had recently won a gold medal. But then he laughed again and told me not to get too excited; the gold medal, he told me, came at the San Antonio Rodeo Wine Festival.

One of the more troubling practices (though I’ll admit that it may be a function of carelessness) is having a shelf-talker that doesn’t match the vintage of the bottle being sold. I’ve seen that at Kroger with some frequency. Kroger’s shelf-talkers do tell the vintage of the bottle that the review applies to (well, at least usually), but it is not always easy to find the vintage on the shelf-talker. Many times I’ve seen a shelf-talker telling me that a particular wine had a good rating only to discover that the shelf-talker and rating were for the previous vintage, not the vintage actually for sale. If both vintages received good ratings, then again, “no harm, no foul”. But if the vintage being sold received a worse rating, especially a much worse rating, then is it fair for the store to use that old shelf-talker? I wonder the extent to which the average consumer recognizes the difference in quality from vintage to vintage and that a 91 rating for 2007 may not translate to another 91 rating for 2008. I suspect that in most cases this is a case of carelessness; the original shelf-talker was printed when the wine was first put on the shelf and nobody took the time to replace that shelf-talker when bottles of the new vintage were added. But is that kind of carelessness acceptable? After all, we don’t accept it as acceptable carelessness for a store to continue to sell meat or other products beyond their expiration dates. And we certainly wouldn’t view it as acceptable for a store to put a false expiration date on a loaf of bread or carton of milk.

I’ve also seen the inverse of this problem. Recently at Costco, I saw a shelf-talker that mentioned the 2006 and 2007 ratings (both of which were good). The problem was that the wine being sold was the 2005 vintage. Hmm. That doesn’t strike me as the same kind of carelessness. Is it simply an effort to provide the consumer with some kind of information upon which to base a decision? Or is it something less noble?

Finally, I want to address a very specific instance of the use of a shelf-talker that I recently encountered that was, in my opinion, the most deceptive use of a shelf-talker that I’ve ever seen. In fact, this particular shelf-talker went beyond mere carelessness or somewhat deceptive sales practice to outright consumer fraud.

On February 13, 2010, I visited the Fresh Market at 2490 E. 146th Street in Carmel, Indiana. I enjoy taking a few minutes to look at the wines that are available. In the rear of the store, just across from the seafood counter, was a freestanding display stand with several wines. What I saw caused my jaw to drop. Here’s a photograph of the shelf-talker that I saw (note that this photo was actually taken on February 26; the display had changed slightly [more on that below], but the shelf-talker appeared to be the same):

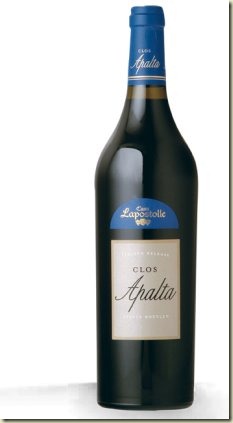

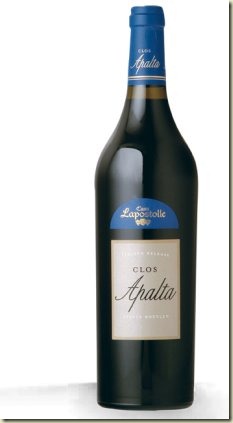

So what’s wrong with this shelf-talker? Here’s a photo of Wine Spectator’s #1 Wine of the Year for 2008:

So what’s wrong with this shelf-talker? Here’s a photo of Wine Spectator’s #1 Wine of the Year for 2008:

Do those bottles look the same? Nope. The wine for sale at Fresh Market is the Casa Lapostolle Cabernet Sauvignon Rapel Valley 2007. Wine Spectator liked the wine and gave it rating of 86 (the link may be password protected; sorry). But it wasn’t the 2008 Wine of the Year. That honor went to another wine from the same Chilean winery: Casa Lapostolle Clos Apalta Colchagua Valley 2005 (a blend of Carmenère, Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, and Petit Verdot). That wine received a rating of 96 and has a suggested price of $75. While an imperfect analogy, it’s a bit like telling a consumer that the Chevy Cobalt available at the local dealer is the car that won the Daytona 500! A Chevy may have one, but it certainly wasn’t the one on the dealer’s lot.

Do those bottles look the same? Nope. The wine for sale at Fresh Market is the Casa Lapostolle Cabernet Sauvignon Rapel Valley 2007. Wine Spectator liked the wine and gave it rating of 86 (the link may be password protected; sorry). But it wasn’t the 2008 Wine of the Year. That honor went to another wine from the same Chilean winery: Casa Lapostolle Clos Apalta Colchagua Valley 2005 (a blend of Carmenère, Merlot, Cabernet Sauvignon, and Petit Verdot). That wine received a rating of 96 and has a suggested price of $75. While an imperfect analogy, it’s a bit like telling a consumer that the Chevy Cobalt available at the local dealer is the car that won the Daytona 500! A Chevy may have one, but it certainly wasn’t the one on the dealer’s lot.

How many people bought a bottle of that 86-rated Cabernet Sauvignon thinking that they were getting an incredible buy on the 2008 Wine of the Year?

When I saw this shelf-talker I was furious because I worried about how many people would be mislead. (I knew what the 2008 Wine of the Year was because I happen to read Wine Spectator and enjoy reading about the top wines that I’ll most likely never get to try.) I walked over the store’s main wine section to see if the misleading shelf-talker was repeated. It wasn’t. Instead, I saw this shelf-talker:

Note that while this shelf-talker (obviously produced by the winery or its distributor, not Fresh Market) is being displayed on the bottle of Cabernet Sauvignon, it clearly highlights the Clos Apalta. So a customer who was shopping in the main wine section of Fresh Market would have seen this piece of advertising as opposed to the clearly false shelf-talker at the other side of the store. One other thing to be noted: If you look at the first photo above (which, recall, was taken on February 26, not February 13), you’ll see a bottle (at the far right) with the advertising shelf-talker displayed above (along with another advertising shelf-talker). However, when I first encountered the misleading shelf-talker on February 13, it was the only shelf-talker in use for the Casa Lapostolle wine on that display.

Note that while this shelf-talker (obviously produced by the winery or its distributor, not Fresh Market) is being displayed on the bottle of Cabernet Sauvignon, it clearly highlights the Clos Apalta. So a customer who was shopping in the main wine section of Fresh Market would have seen this piece of advertising as opposed to the clearly false shelf-talker at the other side of the store. One other thing to be noted: If you look at the first photo above (which, recall, was taken on February 26, not February 13), you’ll see a bottle (at the far right) with the advertising shelf-talker displayed above (along with another advertising shelf-talker). However, when I first encountered the misleading shelf-talker on February 13, it was the only shelf-talker in use for the Casa Lapostolle wine on that display.

Before I finished my shopping that day, I encountered saw a Fresh Market employee that I guessed to be the manager. I asked him if he was the manager and he confirmed that he was. I explained the problem with this particular shelf-talker to the manager. He seemed to understand, but didn’t seem to take it too seriously. I then asked him how many customers might have bought this wine thinking that they were buying something else entirely and whether that was fair. Then he seemed to get it. He said that he’d “look into it” but told me that “these things” are handled by the “wine guy” at the corporate office.

Last weekend (February 20 or 21) my wife was at that Fresh Market. I asked her to look for the misleading display and she confirmed that it was still in place. So twice this week, for no good reason other than the fact that I was angry, I called Fresh Market’s corporate number to complain. Each time, the voicemail system directed me to a mailbox that was full. On February 26, I went back to the Fresh Market. The misleading display was still present (though the display stand had been rotated) and the additional advertising shelf-talkers had been added to a few of the bottles. In addition, back in the main wine area, another large display had been set up:

The misleading shelf-talker is not used on this larger display. What is worth noting (remember the discussion above changing sources) is that the big shelf-talker in this photo refers not to Wine Spectator (which gave the wine a rating of 86), but rather to Wine Enthusiast which gave the wine a rating of 90. Gee, I wonder why Fresh Market used Wine Enthusiast here instead of Wine Spectator?

The misleading shelf-talker is not used on this larger display. What is worth noting (remember the discussion above changing sources) is that the big shelf-talker in this photo refers not to Wine Spectator (which gave the wine a rating of 86), but rather to Wine Enthusiast which gave the wine a rating of 90. Gee, I wonder why Fresh Market used Wine Enthusiast here instead of Wine Spectator?

I’m not sure what more to say (I know, I know; I’ve said enough already). Fresh Market is advertising a product in a highly deceptive, even fraudulent way. The store manager has been told about the problem, but it has not been remedied. I can only wonder whether there are other similar issues at Fresh Market; can I believe anything that they tell me or is a lie an accepted part of the Fresh Market business model? I understand that mistakes happen. Perhaps the shelf-talker was a originally a mistake. But for the deceptive shelf-talker to remain for two weeks after the manager was told about the problem takes this out of the realm of mistake and into the realm of … um … something else, something far worse.

On the whole, I still like shelf-talkers. They give me some ideas and help me compare one wine to another. However, I’m always very, very cautious because of the frequency that they are untrustworthy. I think that retailers should use shelf-talkers judiciously, but they should be careful that the shelf-talkers that they use are accurate. The goal should be to help the consumer, not mislead; to sell, without cheating. On the whole, I think that retailers will, in the long run, make more money by treating consumers fairly and providing helpful information rather than by failing to provide information, providing incorrect or deceptive information, and making the quick buck at the expense of customer trust.

What do you think of shelf-talkers? Do you read them? Do you rely on them? Have you seen deceptive shelf-talkers? Let me know.

Labels: Business, Wine